Law of Accelerating Cost

Executive Summary: America’s economic growth has been in decline for decades and some feel nothing can be done. The “Law of Accelerating Cost” (LAC) postulates that to maintain economic growth as a constant percent of GDP, exponentially more R&D resources over time are required. We have not been making these investments since the 1970s. These resources can be effectively obtained in three ways:

- Increased federal and corporate investments.

- Better use of existing funds by using value-creation best practices.

- Movement away from areas of low economic return to focus on areas of major impact to the economy.

An important part of the solution that addresses our economic decline lies in satisfying these factors. The largest and most efficient solution is achieved when these factors are combined.

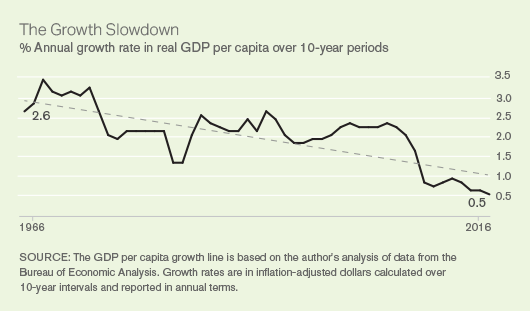

Decline: Many important U.S. economic indicators, such as the rate of GDP growth[1] and economy-wide return on investment, show continuous decline since the 1970s.[2] The labour participation rate is in dropping[3] and the middle class is shrinking.[4] Of the 10 million jobs created from 2005 to 2015 almost none were traditional 9-to-5 jobs. A recent study found that 94% of net job growth from 2005-2015 were in the non-traditional category with over 60% due to independent contractors, freelancers, and company supplied temporary workers.[5]

This decade-long decline has been surprisingly independent of political parties, recessions, bubbles, and major world events. What is going on?

New Normal: Robert Gordon argued that most of the important innovations, such as electrification, the airplane, and the refrigerator, have already been invented, so reduced productivity and growth is to be expected. He also lists six “head-winds,” that are dragging the U.S. down: demography, education, inequality, globalization, energy/environment, and consumer and government debt.[6] These are serious issues that must be addressed. Larry Summers says our performance is simply the “new normal”[7] – i.e., permanent secular stagnation.

But what else might be driving these long-term trends? And what might we do?

Technology and Globalization: Since the 1970s, when many of the downturns started, globalization and technology have played increasingly powerful roles. Interestingly, that was the start of the microprocessor revolution. Intel introduced the first microprocessor, the 4004 in 1971, and consumer products like the game “Pong” started to proliferate. President Nixon’s China opening in 1972[8] signified the emerging importance of the global economy.

Information technologies improve at rapid exponential rates, so they are powerful forces for change, as exemplified by the Internet and today’s personal computing devices, which are more powerful than supercomputers in the 1960s.[9] And the next wave of manufacturing automation and driverless vehicles foretell serious joblessness challenges.

Global competition, although it is just beginning, has increased almost as fast over this time frame. There are hundreds of millions of brilliant people yet to join the global economic Olympics.

Regulations: Other negative economic influences include the tsunami of U.S. government regulations, which cost over two trillion dollars a year in a $16 trillion per year economy.[10] Many of these are non-productive rules that limit competition[11] or are dead costs for the overall economy. If we assume that 25% of such regulations are unnecessary and selectively eliminated them, another $500 billion of resources could be used more productively across the economy.

Worker Involvement: Only a tiny fraction of companies and government agencies use value-creation best practices for creating new products and services. Because of this and a host of reasons, including poor management, most employees are unmotivated and likely less productive than they could be. Gallup determined that only 33% of U.S. corporate employees are engaged,[12] while 17% are actively disengaged.[13] For government workers, the results are even more depressing: only 29% are engaged.[14]

Stock Buybacks: Other practices are damaging. Since the 1980s companies have been investing more in their own stock than in creating new businesses, products, and services. Steve Denning persuasively argues that such practices are both irresponsible and significant in holding down growth and prosperity.[15][16] Buybacks can make sense when a stock is undervalued, but buybacks often take place to mask other business problems when the stock is overvalued.[17]

Just in the twelve months ending in October 2016, the S&P 500 bought back $560 billion in stock.[18] Since 2004 the astounding total of almost seven trillion dollars has been spent on stock buybacks.[19]

These stock buybacks are a financial bonanza for stockholders and senior managers, but they create little to no new economic value for society. It had previously been illegal for companies to buy their own stock because it was considered to be insider trading,[20] but the law was relaxed in 1982.[21] Creating sustainable value, as opposed to buying your own stock with cheap money, requires an unrelenting focus on the customer, as championed by Peter Drucker.[22]

Productive Ideas: Still another perspective is provided in a recent paper called, “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?” by Bloom, et al.[23] They test a simple hypothesis: long-term economic growth is due to the number of researchers times their productivity, i.e., the economic worth of their ideas:

Economic growth = Idea total-factor productivity X Number of researchers

Moore’s Law: Bloom et al. look at several examples to test this hypothesis, including Moore’s Law, which tracks the number of transistors on a computer chip over time. For the last fifty years, the transistor count has been increasing by around 35% per year. Kurtzweil calls such positive developments the “Law of Accelerating Returns” (LAR).[24]

The number of researchers required to maintain this growth has gone up by around 7% per year. That is, it takes roughly 25 times more researchers today than in the 1970s for the same percent improvement. Or, if one researcher created one transistor in 1970, that same researcher creates over 50,000 today. The productivity of researchers creating transistors continues to increase exponentially. This percent growth, not absolute numbers, is what matters. That is how we measure and judge progress.[25]

Law of Accelerating Cost (LAC): Thus, there is a Moore’s Law-like effect for the number of researchers it takes to make a constant percent change in performance. But this “law” is negative – it requires exponentially more researchers to keep advancing computer transistor counts at 35% per year. The authors observe that this negative effect is seen almost everywhere across the economy. They also generalize their findings to include other resources, not just numbers of researchers.

I call it the “Law of Accelerating Cost (LAC).” If an innovation does not produce LAR >> LAC, it will likely not make a significant contribution to economic development.

A Different Conclusion: That it takes exponentially more resources over time to create a fixed percent increase in U.S. growth may seem daunting. But it doesn’t mean we can’t grow as fast as we have in the past, at least for the foreseeable future. It means we must either increase the resources provided or improve the impact of our innovations – i.e., our “idea total-factor productivity.”

That is a profoundly different conclusion from claiming we are in a “new normal” or we are out of ideas. We have entered the global innovation economy where progress is often exponential. We should not be surprised that our innovation methodologies must be exponential to keep up. Since we are clearly not creating the innovations needed to improve growth as fast as U.S. society requires, this suggests there is a “new idea” gap that must be addressed.

R&D Investments: Total U.S. R&D spending, including both government and commercial resources, was around $510 billion in 2015, with $360 billion spent by industry.[26] In the U.S., and most developed countries, R&D spending is just under 3% of GPD. Only South Korea is above 4%. Federal government spending on R&D as a percent of GDP has declined sharply. It was over 0.7% in the 1970s and today it is under 0.4%. Corporate R&D has grown significantly over the past decades but total U.S. R&D as a percent of GDP has remained roughly constant. It was about 2.6% in the 1980s and today is about 2.8%.

Total U.S. R&D spending from all sources increases by a few per cent per year, just above inflation. Each year these slight increases allow the media to announce record levels of R&D investment, implying we are responding appropriately.

But if Bloom, et al. are right, there is penalty of around 5-10% per year that must be added across America to create an equivalent percentage of useful idea production. That is, our R&D investments are falling behind exponentially every year. We are not accounting for the Law of Accelerating Cost.

Correcting for LAC: If we assume that a 5% per year increase in investment is needed to keep up with LAC, then R&D investments must be doubled every 15 years. That is, under this general rule, industry would increase R&D from $360 billion to $720 billion per year by 2032. That is a big increase but it makes the $550 billion stock buybacks in 2016 by company CEOs look more damaging. Clearly the corporate financial resources required to increase R&D spending in real terms by 5% each year for decades are available, but they are being misspent.

Poor Performance Today: There are two additional ways to address LAC. The first is to improve our value-creation practices. The work of Practice of Innovation with leading companies around the world shows that less than 20% of their “most important” projects have any real value for the companies. We don’t decide that; we just give them a framework with which to evaluate their projects. Accepting that R&D and innovation are activities where some undirected and serendipitous activity is to be encouraged, the waste of financial and human resources observed is still enormous.

Our experience with national laboratories around the world indicates they generally perform worse than companies. That might sound harsh, since in public most laboratory directors say how productive they are. But in private, most directors are candid about the organizational challenges they face and their real performance. I have talked to directors around the world about this concern, including in the U.S. I asked one U.S. national laboratory director what fraction of the lab’s work had any lasting value for the U.S. and he said, “About 10%.” Even if that was said out of frustration, the performance observed is unsatisfactory. Output from university research is also very mixed. Success is mostly episodic.

Value-Creation Best Practices: One conclusion is that even modest improvements in the use of value-creation best practices can produce major gains. Value-creation initiatives like NSF’s I-Corps, the Agile and Scrum movements, and various design methodologies, like the d.school at Stanford University, are aimed at helping make the value creation process more efficient. Most of these programs are, however, still aimed at creating relatively minor innovations. The value-creation best practices we have developed and share in our workshops, Innovation-for-Impact, are designed to help create major new innovations, like those being advocated in this post.

Globally the use of value-creation best practices is rare, as we have described repeatedly. I generally assume that any company, national laboratory, or government funding agency that is serious about the use of value-creation best practices can improve its performance by at least 100%. That is a conservative estimate because, unfortunately, today’s performance is so poor. When it comes to innovation, there are few upper bounds. There are no physical limits to creativity and ideas.

The fundamentals of value-creation best practices are described here.[27] Across America we need a transformation in value-creation practices like what happened with Total Quality Management (TQM) in the 1970s.[28] Those manufacturing and design practices led to performance improvements of not just two times, but often hundreds of times.

Incremental Innovations: As Bloom, et al. note, some business areas are not open to transformational innovations. With older, established products or services, most companies focus their efforts on incremental innovations, such as a more durable paint for cars, an improved energy-efficient dish washer, a safer car tire, a more efficient manufacturing process, etc. We rarely notice these thousands of innovations but they add up. Occasionally we are pleasantly surprised.

Remember the first time you saw a ketchup bottle turned upside down on a flat top? It solved the problem of getting the ketchup out without splashing it all over the table. This is a valuable innovation that provides new customer value, but its economic impact is small. Such innovations keep their companies in business, fit within their established business models, provide nearer term payoffs, and carry less technical and business risk. However, if these were America’s only innovations, the economy’s overall growth would grind to a halt.

Major New Innovations: The biggest impact on overall economic growth can come from the use of value-creation best practices and the refocusing of ineffective R&D efforts on major unmet opportunities. Major innovations open new market spaces where the impact on society is greatest and where rapid progress can be made without massive numbers of researchers.

Moore’s Law for integrated circuits points the way. Although it continues to cost 7% more each year to keep integrated circuits improving at 35% per year, the value created more than compensates for its increased cost. To increase U.S. economic growth, investments should be increasingly directed toward similar advances. We emphasise the development of innovations where LAR >> LAC.

Abundance of Opportunities: This strategy would not be possible if there were few major new opportunities to be addressed. Fortunately, in almost all areas of technology and business, little of what society wants has been created. Consider the financial industry with block-chain and bitcoin, or healthcare with CRISPR and genomic editing, or autonomous transportation with electric vehicles, or a safe next-generation Internet, or regenerative and personalized medicine, or cost-effective batteries for localized energy production and storage. Because of our increasingly advanced communication infrastructure and software tools, on-line applications are opening major new opportunities, such as in the almost ubiquitous area of the Internet of Things (IOT).[29]

The idea is to find areas where the LAC is either low or zero. Excellent books have been written about the abundance open to us.[30] It seems unlikely we will run out of new multi-billion dollar opportunities anytime soon.

Government Funding: For America to thrive, incremental or even good innovations will not make the difference in economic growth we need. Not only our companies, but also our government funding agencies must change how they select opportunities and manage their projects.

Today DARPA is the best R&D organization in the world.[31] They use best value-creation best practices to identify potentially transformational opportunities, work with researchers from multiple disciplines to create a compelling working hypothesis for the solutions, assemble the best teams to create the solutions, and then proactively manage the initiatives to completion and often commercialization. DARPA works mostly in what is known as Pasteur’s Quadrant,[32] where world-leading research often leads to paradigm-shifting innovations. Those kinds of innovations, like GPS and the Internet, drive meaningful economic growth. The world’s first personal computer assistant created at SRI International, Siri on the iPhone, evolved out of a major DARPA program.

As noted, the world today is full of major opportunities in Pasteur’s Quadrant. But they cannot be identified and then solved effectively unless the best value-creation practices are used. Few do that today. Excelling at the use of value-creation represents a major competitive opportunity for government agencies, companies, or universities.

Progress: Progress at agencies, such as the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), are pointing in this new direction, as well. I have been involved in value-creation workshops with NSF teams to understand their current practices and to help design better practices for the future. Singapore is also exploring ideas along these lines (of which I’ve been part) to significantly increase the impact of its major R&D initiatives.

Almost every other government funding agency has the opportunity for major advances. For example, the U.S. National Laboratories spend over ten billion dollars per year.[33] When mission directed (e.g., programs on national defence) they are essential U.S. resources. With the rare exception, however, they do not use value-creation best practices today. Experience shows that major improvements can be made in many aspects of their research and innovation programs.

SRI Example: This strategy of focusing on important opportunities and using value-creation best practices is what we pursued at SRI International when I was CEO. Using it, SRI created with our partners the first personal assistant, Siri, on the Apple iPhone; HDTV for digital video; Intuitive Surgical for robotic surgery; and SuperFlex for augmented personal mobility, among other important innovations. These innovations created many tens of billions of dollars of new economic value. It is now recognized as one of the most productive research and innovation organizations in the world.[34]

This was also the strategy pursued at Apple by Steve Jobs and now by the management of Google with Alphabet and Google-X. Their recent AI breakthrough, Google Brain, is an impressive example of a transformational innovation.[35] It is also interesting that Google’s China competitor, Baidu, published a paper before Google’s announcement outlining a similar AI solution. Global competition is increasingly fierce. As I have noted, every enterprise must be the best at what it does or go home.

Conclusions: The Law of Accelerating Cost (LAC) highlights the point that incremental or even good innovations will not be enough to get America’s economic growth back to 3% per year. Three complementary actions must be taken:

- Federal and corporate investments increasing by ~5-7% per year in real dollars.

- Broad use of value-creation best practices in companies, government agencies, and universities.

- Increased focus on areas of major impact to the economy – opportunities in Pasteur’s Quadrant.

We must provide greater funding for R&D in both industry and government. Commercial companies have the resources but today they are using many of them non-productively by buying back their own stock. The government should limit those practices. The federal government also needs to increase R&D funding, but that will be hard given how over-committed are federal resources.

But financial resources are not nearly enough. Best value-creation practices must also be used and focused on major opportunities – ones that can move the economic dial. Few companies or government funding agencies use such best practices and many do not spend their resources on initiatives that make a difference. The broad application of such practices would unleash many tens of billions of dollars of wasted resources each year that could be applied to initiatives that matter. They could effectively double, or more, the effectiveness of the financial and human resources being used today.

These observations are preliminary. I appreciate the complexity of the issues and the difficulties involved in changing organizational processes and practices. Other issues, like giving students the skills to thrive in this word, are essential. After all, companies will not invest more until they feel they have the staff and value-creation skills to bring new, high-value innovations to life. In addition, actions that liberate more of America’s resources, such as reforming taxes and regulations, are important. Ultimately all these activities are aimed at unleashing the innovative and entrepreneurial potential of America’s people.

Nevertheless, the core idea presented suggests that economic process is not at a dead end. Rather, to realize our potential and address our economic decline we must adjust our policies and practices to unleash the economic potential in front of us. That requires, in addition to the other factors described, directly addressing the challenges of the Law of Accelerating Cost.

I would appreciate your feedback. This post was stimulated by Pramod Khargonekar, former Director of Engineering at NSF and now Vice Chancellor for research at UCI.

[1] http://www.gallup.com/reports/198776/no-recovery-analysis-long-term-productivity-decline.aspx

[2] http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2013/07/22/how-modern-economics-is-built-on-the-worlds-dumbest-idea/#7665a09656a7

[3] http://www.atimes.com/small-ball-conservatism-national-greatness/

[4] http://www.businessinsider.com/charts-decline-of-the-middle-class-2016-1/#for-context-heres-the-household-income-required-to-be-considered-middle-class-and-upper-class-adjusted-for-household-size-1

[5] http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2016-12-23/top-white-house-economist-admits-94-all-new-jobs-under-obama-were-part-time

[6] http://www.nber.org/papers/w18315

[7] http://larrysummers.com/commentary/financial-times-columns/why-stagnation-might-prove-to-be-the-new-normal/

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1972_Nixon_visit_to_China

[9] http://www.zmescience.com/research/technology/smartphone-power-compared-to-apollo-432/

[10] http://www.nam.org/Data-and-Reports/Cost-of-Federal-Regulations/Federal-Regulation-Executive-Summary.pdf

[11] https://cei.org/sites/default/files/10%2C000%20Commandments%202015%20-%2005-12-2015.pdf

[12] http://www.gallup.com/businessjournal/195803/employees-really-know-expected.aspxg_source=EMPLOYEE_ENGAGEMENT&g_medium=topic&g_campaign=tiles

[13] http://www.gallup.com/poll/188144/employee-engagement-stagnant-2015.aspx

[14] http://www.gallup.com/services/193067/state-local-state-government-workers-engagement-2016.aspx

[15] http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/02/05/salesforce-ceo-slams-the-worlds-dumbest-idea-maximizing-shareholder-value/#2625b3605255

[16] http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/06/09/how-share-buybacks-hurt-shareholders-and-society/#7027718e5d33

[17] http://www.forbes.com/sites/greatspeculations/2016/02/24/how-stock-buybacks-destroy-shareholder-value/#5bf0ac80800d

[18] http://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/ayn-rand-and-corporate-tax-cuts-wont-mend-the-economy

[19] http://www.cnbc.com/2015/09/08/ybacks-are-killing-economic-growth.html

[20] http://www.businessinsider.com/whats-a-buyback-and-why-do-some-investors-hate-them-2016-6

[21] http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/09/14/pocketing-profits-or-reinvesting-them/to-boost-investment-end-sec-rule-that-spurs-stock-buybacks

[22] http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2011/11/28/maximizing-shareholder-value-the-dumbest-idea-in-the-world/#2853a3572224

[23] “Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?”, Nicholas Bloom Stanford University, John Van Reenen MIT, Charles I. Jones Stanford University, Michael Webb Stanford University, November 14, 2016 — Version 0.5 Preliminary and Incomplete.

[24] http://www.kurzweilai.net/the-law-of-accelerating-returns

[25] Curtis R. Carlson and William W. Wilmot, “Innovation: The Five Disciplines for Creating What Customers”, Crown, 2006

[26] https://www.iriweb.org/sites/default/files/2016GlobalR%26DFundingForecast_2.pdf

[27] https://www.practiceofinnovation.com/drucker-forum-on-entrepreneurship/

[28] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Total_quality_management

[29] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_of_things

[30] https://www.amazon.com/Abundance-Future-Better-Than-Think/dp/1451614217

[31] http://www.darpa.mil

[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pasteur’s_quadrant

[33] https://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2016/02/f29/FY2017BudgetinBrief_0.pdf

[34] http://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2015/11/30/how-to-create-an-innovative-culture-the-extraordinary-case-of-sri/#6a4e7083370d

[35] http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/14/magazine/the-great-ai-awakening.html

2 Comments

Dr. Henry Kressel

The focus on inefficient management of innovation resources is surely one of the key elements in growing GDP through new products and services. However, we need to differentiate between the GDP growth in the developed countries (like the US and EU) and in the developing countries, primarily in Asia where GDP growth has exceeded that of the US because of the growth of a modern economy and export led investments in manufacturing. As David Goldman and I pointed out in our recent OpEd in the Wall Street Journal (November 21, 2016), the move of many growth industries to Asia (such as consumer electronics,for example), acts as a brake on investment in the former home countries. As a result, if the product delivery business does not stay in the home country, investments do not contribute to local GDP and employment.This is happening in electronic infrastructure products as well such as telecommunications systems and as a result, investment in innovative new products is slowing dying out in the US and EU as Huawei in China has become the dominant supplier of such high performance products. To reverse that trend requires that corporations and the US development funding agencies focus on certain industries and commit to keeping the product making and delivery domestically. The car industry was saved through government assistance in recent years–is that a model for the future?

Curt

Thanks. These are important points. There are many other aspects to this story and those are critical ones. Other colleagues wondered how universal is the Law of Accelerating Costs at the national level? There are obviously endless exceptions at the company level. Answering that question requires more studies — it is a working hypothesis at this point. My intent was to look at several elements that impact our rate of creating new innovations and see if the financial resources (including stock buybacks), human capabilities (when using best practices), and market opportunities (for major innovations) were sufficient to move the national economic growth dial. My conclusion was yes, it is possible. That is very different than Gordon and Summers implying that little to nothing can be done. Nevertheless, making these changes and the ones described by Henry Kressel are daunting. Perhaps the most significant impact would be achieved by having the U.S. government limit the conditions under which companies can buy back their own shares. Other thoughts?